Can justice truly define good and evil after war?

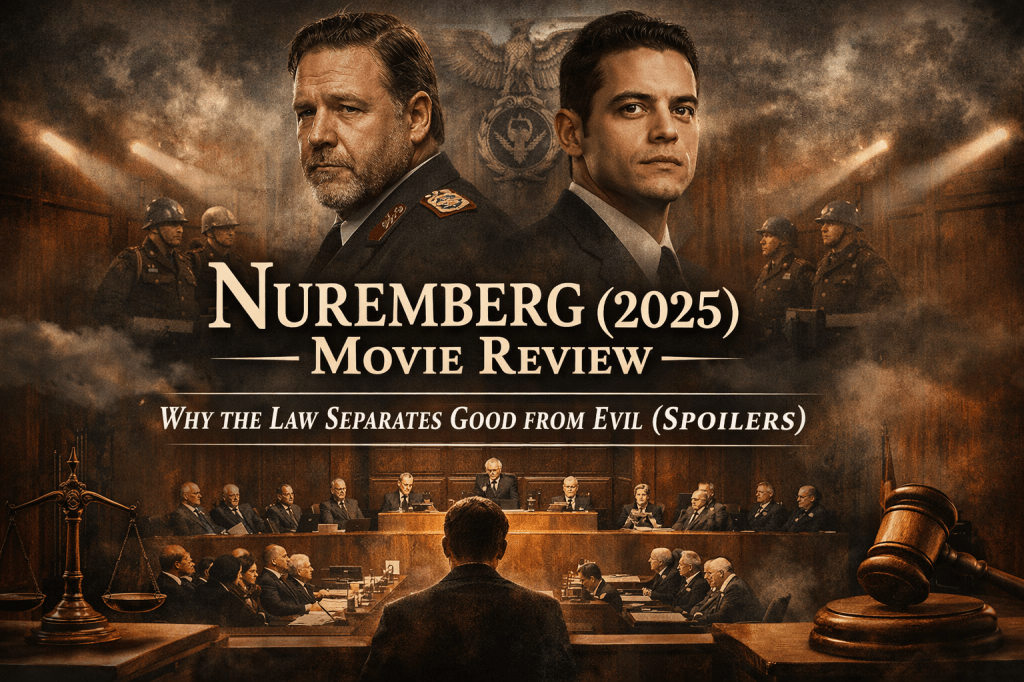

I recently watched Nuremberg, a historical drama that should not be confused with the classic Judgment at Nuremberg (1961). This film is adapted from the book The Nazi and the Psychiatrist by Jack El-Hai and explores the psychological, legal, and moral foundations of the Nuremberg Trials following World War II.

The film carefully explains how the trials were conceived, approved, and ultimately executed, emphasizing their historic importance in bringing a permanent legal reckoning to the atrocities committed during the war. More than a procedural account, Nuremberg examines why law is necessary to draw a clear boundary between good and evil, even when emotions and revenge might seem justified.

The Nuremberg Trials: Justice as a Moral Line

The Nuremberg Trials were not merely an act of retribution by the Allies; they were a deliberate effort to distinguish rule of law from fascist barbarism. High-ranking officials of the German Reich—those who could not escape—were prosecuted for crimes against humanity so the world could confront, in undeniable terms, the horrors of the Holocaust.

Graphic images and testimonies were presented not only to condemn the perpetrators, but to educate humanity, ensuring these crimes could never be denied nor forgotten. The trials set a precedent: even in the aftermath of total war, justice must prevail over vengeance.

This message resonates powerfully today. History may not repeat itself exactly, but—as often attributed to Mark Twain—it rhymes. Remembering history is not an academic exercise; it is a moral necessity.

Law, Even for the Devil

One of the film’s strongest philosophical underpinnings is captured in a quote attributed to Thomas More, paraphrased in spirit:

“I would give the devil the benefit of the law, for my own safety’s sake.”

This idea encapsulates the essence of the Nuremberg Trials. If the law is abandoned when it is inconvenient, then no one is protected when power shifts. The film succeeds in explaining why even the most monstrous criminals must be judged within a legal framework.

Psychology of Evil: Göring and Douglas Kelley

Beyond legal history, Nuremberg delves into psychology through the tense relationship between Douglas Kelley, portrayed by Rami Malek, and Hermann Göring, played by Russell Crowe.

Kelley’s psychoanalysis of Göring reveals something deeply unsettling: evil is not always driven by madness. Göring is intelligent, manipulative, and fully aware of his actions. Their evolving relationship, paradoxically, ends up helping Göring maintain psychological control—culminating in his suicide just before his scheduled execution after his conviction, allowing him to evade final accountability.

A Warning the World Ignored

After the trials, Kelley publishes his findings and issues a chilling warning: fascism is not uniquely German. Under the right conditions, it can arise anywhere. Tragically, his message is dismissed. Exhausted, disillusioned, and ignored, Kelley ultimately takes his own life—an outcome that underscores the film’s bleak conclusion.

The war ended, justice was served, but the deeper lesson was shelved.

Final Verdict

⭐ 4 out of 5 stars

Nuremberg is a compelling, well-acted historical drama with a star-studded cast and a thoughtful, original approach to a familiar subject. More importantly, its message feels disturbingly current: the fight between good and evil often ends in a courtroom, but it never truly ends.

If you are interested in World War II films, legal history, or philosophical reflections on justice and morality, Nuremberg is well worth your time.

Enjoyed this review?

If you found this post useful:

- Like it

- Leave a comment

- Share it with other movie lovers

Follow me on X: @jamendezr89

Instagram: @ontheside89

Subscribe to the blog to receive new reviews and essays directly in your inbox.